On the road from Amman to the Syrian border, we overtake aging compacts and minibuses. Mattresses, boxes and furniture are piled up metres high on their roofs. You can tell from the license plates of the vehicles that they are returnees. Not that long ago, over 700,000 Syrian refugees were living in Jordan alone. Now thousands are returning. As soon as they cross the border, something unexpected awaits them: the border posts are all decked out, a revolutionary song from 2011 can be heard from loudspeakers in one hall. Displays not only provide information about a fast-track entry procedure - they also greet the arrivals with words until recently unthinkable: "Welcome to Syria, your homeland has missed you", and: "Syria is the beginning: Be part of its bright future".

We are also greeted in a friendly manner by the men at the checkpoints. They are wearing an HTS badge, but no uniform. We pass burnt-out tanks and demolished checkpoints. Our driver tells us that the secret service used to be in charge here. You always had to put up with harassment and people were frequently arrested at the checkpoints. The "before" he is talking about was just seven weeks ago. President Bashar al-Assad's regime collapsed at the beginning of December 2024. No one could have predicted it. And the old has indeed disappeared. But has the new Syria already begun?

The new old capital

We reach Damascus. In the capital, the traces of the uprising are unmistakable. The migration and passport office is burnt out, and torn and shredded posters of Hafez al-Assad adorn the floor of the reception area in the gutted Baath Party headquarters. The building is poorly guarded, with three young HTS fighters standing around a fire drum smoking cigarettes. The eastern suburbs of Ghouta have been razed to the ground. Once home to 500,000 people, the area was largely under the control of opposition militias for several years during the civil war. The regime bombed the area into rubble with Russian support. In 2018, hundreds of thousands of residents were able to evacuate to Idlib.

Away from the ruins, however, life is pulsating. People push their way through the al-Hamidiya bazaar, the old town is teeming with families, young people take selfies with HTS militiamen. It seems as if everyone wants to usher in the new Syria and be part of it. In the cafés and restaurants, however, only a few seats are taken. Many simply cannot afford to go there. The country's economy is in shambles and food prices remain high. This makes the public squares all the more important. They are a key hub as the regime's atrocities are subjected to closer scrutiny and analysis.

In the days following the opening of the prisons, Al-Marjeh Square became a forum of last hope: desperate mothers hung up photos of their missing sons and daughters and left telephone numbers there. Maybe their child was still alive after all, maybe someone would recognise the person in the photo. There are over 120,000 documented disappearances, but the number of unreported cases is far higher. At the same time, the present and future of the country are also being contested in the squares. Today, a vigil for the protection of minorities is taking place on Al-Marjeh Square. Will everyone find a place in the new community that is being built in this multi-ethnic and multi-religious country? Will everyone find protection? We also hear reports about attacks on and persecution of Alawites, the ethnic group of which al-Assad is also a member. Syria is a country full of wounds and "scores to be settled".

Activists, intellectuals and returnees from Europe meet at Café Rawda. In the past, you could be sure that a state security agent would be sitting at the next table. But now, for the first time in ages, people can talk openly and rejoice. Everyone present is inspired by the fact that the door has been opened toward a better and peaceful future for the country. And everyone is keenly aware that civil society and all those who have been fighting for a democratic Syria since 2011 have a crucial role to play in seizing this opportunity. Discussions continue late into the night - and the new HTS government is also viewed with skepticism. Too much is known about the Islamists' past and their rule in Idlib. Many see the fact that there was little bloodshed during the takeover as a sign of a possible peaceful future. People do not want to be robbed of the freedom they have finally gained.

What will the path look like? The new rulers plan to set up a committee to discuss the composition of a possible government and the democratisation of Syria in a national dialogue. A new constitution is to be adopted in three years' time, followed by elections in four years. However, criticism is also coming from Syrian civil society, reports medico partner and women's rights activist Huda Khaity. Decision-making processes and the composition of the committee lack transparency.

Syria's hell

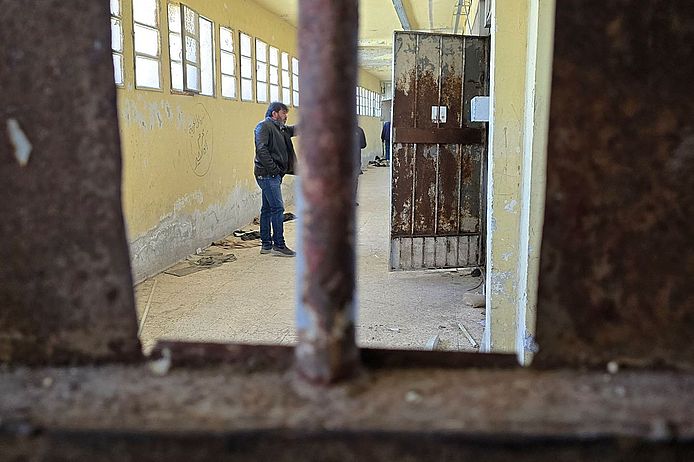

North of Damascus, in the midst of shimmering golden mountains, lies the dreaded Sednaya military prison. Mainly political prisoners were held here and tens of thousands died in the years after 2012. On 8 December 2024, 2,000 prisoners were freed from their cells. The flag of the Syrian revolution is painted on the walls of the entrance gate, underneath is written "The human slaughterhouse - We will not forget, we will not forgive". We follow the road as it winds its way up the slope to the main building. In front of the entrance to the terrifying building, the concrete pavement has been broken up. Secret cells were also searched for here. As we enter the complex, the smell of decay invades our nostrils. There is the field court where thousands of death sentences were passed; there are the cages where the prisoners had to wait for their sentences; there is the courtyard where the executions took place.

The closer we get to the concentration cells, the more acrid the stench becomes. Up to 100 people were locked up at a time in these dark rooms, perhaps 20 square meters in size. Later, survivors will tell us about the system of terror, about every conceivable form of interdiction, denunciation, rape and torture. For the prisoners, it was not about surviving. It was about dying as quickly as possible. Nobody really knows what will become of this place of horror. Justice and a thorough investigation, with the involvement of the victims, punishment of the perpetrators, regardless of whether they have fled abroad or are still living in the country - that is what many people want. There is a long way to go.

Lawyers in the underground

Back in Damascus. We light our way through a dark stairwell with our cell phones. We meet the lawyers Jihan, Hussein, Adil and Amar in an office. It is a special moment. For the four of them, it is the first face-to-face meeting in a long time. "We were all imprisoned in this country," says Hussein. "I could never have imagined that we would one day meet in our own office with an international human rights organisation." We talk for hours. There is a lot of laughter, but also tears. The Syrian revolutionary flag hangs on one wall of the office.

The four are part of the network of lawyers at the Center for Legal Studies and Research (The Center) supported by medico. Some members have performed human rights work from exile in recent years, including the lawyer Anwar al Buni, who has conducted proceedings against Syrian offenders before European courts working from Berlin. The others worked underground in Syria, sometimes risking their lives in the process. For as long and as best they could, they provided detainees in civilian prisons with money, clothing and hygienic products, acted as counsel for political prisoners and tried to prevent death sentences from being carried out. They were able to secure 23 acquittals and repeatedly found ways to conduct trials within the corrupt system.

They were often the only connection to the outside world for the prisoners. Some of them kept in touch even after their liberation. But many are finding it difficult to get back on their feet again, says Hussein. These are people like Sinan, who was accompanying us in Damascus. In 2011, he became involved in the civil resistance at the age of 23. The system's henchmen caught him and he was sent to a state security torture prison. He survived, and because his family forked up money, he was transferred to Adra civilian prison. He spent a total of twelve years in prison and was freed six weeks ago. He still does not speak Assad's name out loud. "I have to get used to freedom again," he explains.

"There are thousands of cases like this," reports Amar, pointing to the dozens of cardboard boxes piled up all over the office rooms. Some of them contain documents from Sednaya. Amar opens a folder and pulls out documents: court sentences, prisoners' ID cards, guards' badges, lists. The lawyers were able to secure hundreds of thousands of files from the regime's repressive apparatus. They have already trained teams of volunteers to help process the documents in accordance with international standards. The creation of a database is key to the criminal justice investigative process and what is known in the trade as "transitional justice". The HTS government has supported this process to date. But the team at The Center is not just looking back. It is also keeping a close eye on what is currently happening in Syria. Human rights violations are still being committed, whether in the form of arbitrary arrests or extrajudicial killings. The lawyers are convinced that these, too, must be punished. Because there can be no real democracy without a fair judiciary. As Jihan puts it: “The crimes of the Syrian regime must not be committed with new hands.”

What remains of Rojava?

The situation is completely different in our visit to Rojava. Our first stop is the large city of Qamislo. It is true that the region has been de facto self-governing since an agreement concluded in 2012, when the regime withdrew and left it to the Kurdish Self-Defense Forces (SDF) to fight the militias of the "Islamic State". The dictatorship was by no means absent, however. It was in control of Qamislo airport and individual districts until the very end. In addition, Syrian and Russian military forces were stationed in the region as a result of Turkish attacks carried out in 2019, based on an agreement the self-government was forced to enter into in its fight for survival. And today? The remains of a demolished statue of Hafez al-Assad lie scattered about in a traffic circle. The fact that no one here mourns the Baath Party is the result of a long history. For decades, the Kurds were only granted limited rights and the north-east was deliberately kept underdeveloped. Instead, government projects sought to "Arabise" the region. In the Arab-dominated cities, there is therefore also support for the new HTS government. Old anti-Kurdish resentments are fermenting once again as well.

In Qamislo, we meet medico partners and many old acquaintances. The uncertainty surrounding the new Syria is even greater here than in Damascus. The pain and experiences with al-Nusra, the predecessor organisation of HTS, and all the other radical Islamist groups are too deep-rooted to be swept away by the joyful exuberance in the rest of the country. The skepticism is fuelled by news like a leader of an Islamist militia that deliberately murdered the Kurdish politician Hevrin Khalef in 2019 has been appointed to the transitional government. Nevertheless, initial talks have taken place with the HTS government under the leadership of SDF commander Mazloum Abdî, and declarations of intent are giving rise to a glimmer of hope. But words must be followed by deeds.

It has in the meantime become clear that neither representatives of the self-administration of north-east Syria nor other minorities will be part of the national transition committee. However, the Kurds will not be able to get around negotiating with the new government. At the same time, there are red lines. It is about rights to political freedom, the administration of the cities, a fair distribution of resources and the question of the future role of the SDF. The self-administration is now organising an internal dialogue process with this in mind. "No one will give up what they have been fighting for here over the last ten years - especially not women's rights," Evin tells us at a meeting in Hasakeh. She was part of the local government's women's commission. There is currently equal representation for women in leadership positions in Rojava. There are laws to protect women against violence, multiple marriages are banned, and women and men have equal opportunities in education and the military. Whether all of this will endure in the new Syria is one of many unanswered questions.

Endless displacement

Meanwhile, the threat to Rojava has intensified massively. The Turkish-funded Syrian National Army (SNA), which also emerged from the Free Syrian Army and has occupied parts of the Kurdish areas in northern Syria since 2016, used the advance of the HTS in December 2024 to make renewed forays into the autonomous area. Kurdish units were forced to abandon Tel Rifat/Shebha and the city of Manbij. The city of Kobanê - a symbol of Kurdish self-assertion since the successful expulsion of IS - is now under attack. The offensive has also once again set massive waves of refugees in motion. At the beginning of December, 120,000 people were forced to flee to Tabqa and Raqqa overnight, most of whom had been driven out of Afrin by the SNA just a few years earlier.

With the support of medico, emergency aid workers of the Kurdish Red Crescent have at least been able to set up a makeshift infrastructure. The new arrivals are being quartered in schools, mosques, community centres and stadiums, but also in former regime buildings. Together with our partners from the Kurdish Red Crescent, we visit the emergency shelters in Qamislo and Hasakeh. There are shortages of everything here and the supply of foodstuffs and water is catastrophic. There is scarcely any international emergency aid. There is tremendous solidarity among the local population, however. Many people have made their private homes available for the refugees, collected donations in kind and organised activities for the children.

The next stop is the Newroz camp near Derik in the north-eastern tip of the country. It is one of a total of forty refugee camps in the region, all of which are needed, again and again, for incoming displaced persons and refugees. The camp administration does not have much time for us: almost 16,000 people are currently living here, with more arriving every day. 51 families have just arrived from the cities of Raqqa and Tabqa. There are not enough tents and the infrastructure for sanitary facilities and relief supplies is inadequate. Nevertheless, men and women are unloading their belongings from large trucks.

It is not much. A desperate woman stands in front of us. She tells us that she had to flee from the Islamists in Shebha. In Tabqa she slept on the street, in Raqqa in a school. "We have fled across all Syria and yet we still face oblivion."

Suddenly there is excitement. The next piece of bad news has arrived: Trump has stopped US development aid by decree. It is not yet clear what this means for the people here, who already fear the withdrawal of US troops. But bad things must be feared. So far, US money has been used to pay for bread and water and the administrative staff. Over the next few days, we will receive repeated reports that employees of local aid organisations funded by USAID have been given notice by email, curtly and to the point. Our companion Ossama estimates that just under 300 people will be affected. There are at least 500,000 people in the region who are being supplied with aid money. He himself was involved in an ecological development project and is now unemployed.

There is an ambivalent feeling in the air as we bid farewell. The fall of the regime has shifted the coordinates and opened up new spaces. It is not yet clear where Syria is heading. But while people in large areas of the country now have something to gain, in the north-east it is important not to lose even more, if not everything.

Since 2011, medico has been supporting those who have not given up on a democratic Syria despite the civil war and terror - from Rojava to Damascus. The focus has been and continues to be on providing emergency aid, investigating crimes, offering healthcare and strengthening feminist struggles.

Whether it is the "Solardarity" donation campaign or the MENA Prison Forum, articles or podcasts: medico is also trying to maintain interest in, and solidarity with, the region here in Germany. This is only possible thanks to your tremendous willingness to donate.