By UMAM (Documentation & Research)

On April 13, 2025, Lebanon and its civil society commemorated the 50th anniversary of the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War. Although commonly referred to as a "fifteen-year war," the country’s ongoing dynamics raise doubts as to whether it has ever truly ended.

On this day in 1975, a passing car opened fire on a procession during the inauguration of a church in the predominantly Christian neighborhood of Ain Al-Rummaneh in East Beirut. Several hours later, a retaliatory attack was launched on a bus carrying Palestinian passengers driving through the same neighborhood, killing most of the passengers. However, as in many conflicts, these events were merely the spark that ignited existing deep-seated tensions in the country .

Lebanon was, and remains, shaped by a political system based not only on religious affiliation but also on a rigid system of confessional “parity:” power is divided based on supposedly fixed demographic ratios. An oral agreement, known as the “National Pact,” officially split power between Christians and Muslims in 1943, though in practice it handed dominance to established Christian elites, neglecting other communities, particularly the Shiites. Confessional identities had long been exploited and polarized by political actors, well before the war began.

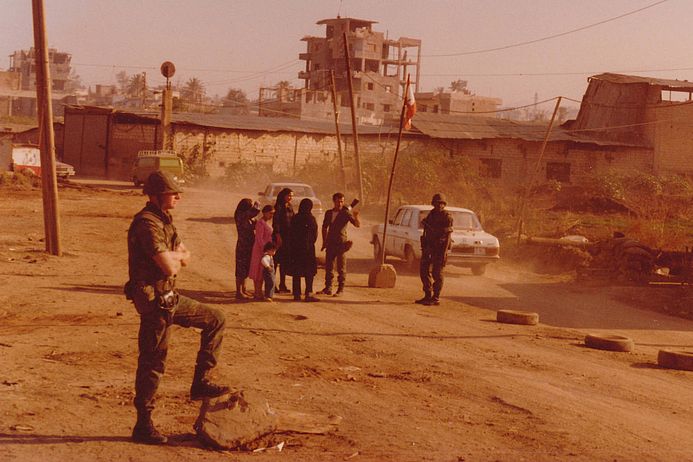

Internationally, Lebanon was a strategic focal point for various players—before, during, and after the war. With the influx of over 100,000 Palestinian refugees in 1948 and the relocation of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) headquarters to Lebanon in 1970, the country became a battleground between the PLO and Israel. This led to several phases of intense violence and Israeli occupation, particularly in 1978 and 1982. The latter resulted in the establishment of an Israeli-controlled so-called “security zone” in southern Lebanon that lasted until 2000. Syria, which saw itself as Lebanon’s protector, also intervened militarily from 1976 and remained present until withdrawing its troops in 2005. Both interventions lasted beyond the official “end” of the war.

The Civil War is estimated to have claimed around 150,000 lives and led to internal displacement and mass emigration, producing a new spatial order along confessional lines. Militias took over state functions,providing social services, security, and judicial structures within their respective territories. Violence became central to securing power and territorial control. The confessional system, originally intended to foster coexistence, instead entrenched divisions during the war and marked a shift from fragile coexistence to mutual exclusion.

Taif and the False Settlement

The Civil War officially ended in 1990 with the Taif Agreement; often described as a peace treaty, it was in fact a power-sharing compromise intended to stabilize the confessional divisions, albeit one that failed to bring about a comprehensive peace. Instead, it sought to "civilize" the logic of the Civil War rather than overcome it. The confessional structure remained largely untouched and continued to misrepresent actual demographic realities.

Taif quickly became a tool of state-imposed amnesia, reinforced by old and new mechanisms of confessional division, foreign interference, and ongoing political violence. Warlords remained in power, political discourse remained fragmented,and confessional veto mechanisms hindered political reforms.

At the same time, Lebanon remained a stage for geopolitical proxy conflicts. Hezbollah’s monopoly on armed resistance against Israel tied Lebanese sovereignty to regional dynamics—especially those influenced by Syria and Iran. After the withdrawal of Syrian troops, Hezbollah expanded its influence across all major state institutions at both national and local levels—including the judiciary—and resorted to violence, including assassinations, when its interests were at stake.

Furthermore, collective memory was selective, shaped by confessional narratives and contested truths. Transitional justice mechanisms, such as truth commissions or war crimes tribunals, were never established. Instead, a blanket amnesty law was passed in 1991, cementing a culture of impunity. Mass graves remained untouched, and the fate of thousands of missing persons was never clarified.

Dealing with the Past and Remembrance

In this vacuum, civil society gradually carved out spaces for exchange, critical research, dialogue, and remembrance—to confront a past that had been deliberately ignored from above. A central actor in this effort has been our organization UMAM Documentation & Research (UMAM D&R), founded in 2005 by Lokman Slim, a Lebanese Shiite intellectual and publisher, and Monika Borgmann, a German journalist and filmmaker. As a research and civic center, UMAM D&R engages with Lebanon’s conflict-laden past to foster critical reflection on the country's history, and serves as a foundation for debate on its present and possible futures.

One of UMAM D&R’s defining focus areas is on prisons and carceral experiences in the Middle East. This focus emerged with the 2016 documentary film Tadmor, produced by Borgmann and Slim. . In the film, former Lebanese inmates of the notorious Tadmor (Palmyra) prison in Syria re-enacted their detention experiences. By confronting their trauma and pain, they reclaimed agency by playing both prisoners and guards and speaking for those who no longer could. This project sparked a wave of further initiatives from UMAM D&R, including the theater piece The German Chair, the publication of witness testimonies, and numerous public events. Personal narratives were always paired with political demands and a focus on suppressed dynamics, such as the long-term Syrian military presence in Lebanon or the many forms of impunities in both countries

In addition to Tadmor, UMAM D&R launched projects like Missing… And They Never Came Back, focusing on Lebanon’s forcibly disappeared, and the MENA Prison Forum (MPF), which explores prisons in the MENA region as sites of repression and resistance. In light of Lebanon’s deepening crisis and with an awareness of the value of safe spaces and global perspectives, we also opened an office in Berlin to engage in dialogue with German, Arab, and international audiences and to foster exchange within the MENA region.

New Crises and Glimmers of Hope

Beyond the structural challenges of remembrance and accountability, Lebanon continues to face acute crises. In fall 2019, the country suffered a massive financial collapse and witnessed a broad, cross-confessional protest movement against the political establishment. This movement challenged entrenched narratives and sparked hopes for a reformed and de-confessionalized Lebanon. Yet new crises soon followed, namely the Beirut port explosion in August 2020 that destroyed large parts of the capital and killed over 200 people. The explosion has been widely attributed to government negligence and mismanagement, as well resulting from Hezbollah’s role in the country.Most recently, the latest war between Hezbollah and Israel that began in the fall of 2024 has led to widespread destruction and displacement throughout Lebanon and the dismantling of Hezbollah’s leadership, reducing its influence nationally and regionally.

However, in spite of these destructive elements, in recent months, faint glimmers of hope have reappeared. The fall of the Assad regime in December 2024 lifted the fear of the Syrian regime for many in both Syria and Lebanon. The election of President Joseph Aoun and Prime Minister Nawaf Salam, and the formation of a new government earlier this year, are seen by many as a sign of political opening that includes a willingness to critically confront Lebanon’s past.

The 50th anniversary of the April 1975 events offered an opportunity this spring to intensify engagement with Lebanon’s history and present realities. As part of the civil war commemorations, UMAM D&R organized an exhibition and discussion titled 50 Years of Déjà Vu. The central question posed: How can one archive something that hasn’t ended? UMAM also participated in a year-long program under the title Fifty Years of Amnesia by the American University of Beirut (AUB).

Lebanese civil society remains a driving force in these debates and goals of preserving memory, demanding accountability, and working toward a more inclusive historical narrative of a Civil War whose unresolved past renders its supposed end a false settlement.

Monika Borgmann, Bernhard Hillenkamp, Stella Peisch