The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations warns that the impact of the pandemic, together with the swarms of locusts that are hatching in northern Kenya, could endanger the nutritional basis of many people.

medico: Dan, you work for Sodeca in Kenya and you are committed to the realization of socio-economic and cultural rights in Kenya. You are in close contact with the poorest people. What are the social and economic consequences of the Corona measures for the poor and most vulnerable people in the country?

Dan Owalla: Kenya expects the forecast growth in 2020 to decline from 6.2 percent to 3.4 percent. The key sectors most affected include aviation, hospitality, tourism and agriculture. The export sector is also likely to be affected. The closure of borders has affected and partially disrupted trade, including the continued supply of staple foods from Uganda and Tanzania.

In this situation, it is not surprising that those who already had the worst-paid jobs before Corona are now particularly affected by the social consequences of the pandemic: The workers in the informal sector and the casual workers and day labourers in the formal sector. And more than 80% of Kenyans are employed in the informal sector, the majority of them are women. They are also the ones who are additionally affected by the increase in domestic and gender-based violence.

As always, poverty is the biggest health risk: most families in low-income areas, informal settlements and remote areas have no access to basic public services such as water and sanitation, food production and supply is disrupted, and prices for basic foodstuffs are rising insidiously, affecting both the cost of living and health and nutrition. No wonder that people are more concerned about putting food on the table than about COVID-19. In general, there is great hopelessness.

When it comes to daily survival, then you simply cannot afford physical distancing…

Right. A delicate balance must be maintained between containing the pandemic and the continuity of socio-economic activities. How is social distancing supposed to work in regions with high population density? In the metropolises of Nairobi and Mombasa, low-income areas and slums are particularly affected by this difficult situation, as most of the work in the informal sector is done on the street.

Economically vulnerable households in particular are at higher risk of contracting the virus due to the limited space and lack of access to basic services. Although the corona measures implemented so far make sense when viewed in isolation, they have not sufficiently taken into account the more serious impact on low-income households in Kenya, which are in urgent need of support.

Have you been noticing any tensions in public?

The curfew has led to ongoing clashes between the population and the police. Anyone who moves around in public places without a mask is criminalised even though the government is not providing sufficient face masks and other aid for the poor and unemployed.

The military enforcement of the lockdown is an immense problem. The Kenyan police have killed at least six people and have beaten and coerced many more while enforcing a curfew that runs from dusk until dawn. The increasing brutality of the police is not only unlawful but also counterproductive in the fight against the spread of the virus.

What measures should the government take to better protect the population?

Budget funds must be reallocated to provide safety nets for the poor population. Policies are needed to ease the burden on urban areas to ensure that society continues to function amidst social distance requirements and travel bans. Investment in the health sector to effectively combat pandemics is also crucial.

As a human rights organization you have long criticized that access to good health care is only possible for wealthy Kenyans. To what extent was this inequality exacerbated by Corona?

The approach to the pandemic has classified other health emergencies as second-class emergencies. Pregnant mothers who had to give birth during curfew could not go to hospital. People with chronic diseases have great difficulty in accessing health care in health facilities.

You criticize the use of the World Bank's emergency fund. What is going wrong there?

The priorities in the budget allocation were set incorrectly. The uncoordinated hiring of ambulances, the uncoordinated allocation of tea and snacks and the printing of quarantine forms are useless as long as the poor Kenyans have to go into quarantine at their own expense, have to buy masks at their own expense, have to pay for good health care, lose their jobs and stay at home at their own expense. This widens the social gap.

Why is there actually no functioning health structure in a rich country like Kenya?

The promotion of global partnerships as a vehicle for achieving the United Nations' sustainable development goals (SDGs) undermines the primary responsibility of the state to guarantee human rights, including the right to health. The participation of the business sector in multi-stakeholder partnerships "on an equal footing" with governments and civil society organizations, as promoted by the World Economic Forum, offers the opportunity to unduly influence the public health agenda. Businesses can influence partnerships either through their involvement in the governance of partnerships or through their financial contributions, or both. It must be clearly stated that recourse to multi-stakeholder partnerships to achieve objectives carries the risk of encouraging companies' greed for profit.

Shouldn't the WHO play a role as regulator?

That would certainly be true, but WHO, which is an important institution for supporting Member States in implementing SDGs, suffers from structural problems that increase its vulnerability to corporate influence at the expense of public health and public interest. Although the Framework of Engagement with Non-State Actors (FENSA) has some limitations, particularly for the private sector, the implementation of FENSA by the Secretariat has been subject to some tremines. Explicit protection measures and constant vigilant monitoring and advocacy against the influence of companies are therefore necessary.

The interview was conducted by Anne Jung, speaker on health care at medico international

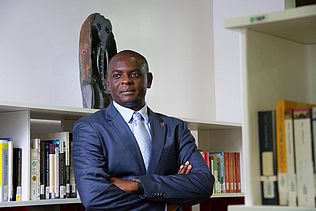

Dan Owalla is a human rights activist and lives in Nairobi. For many years he has worked on police extrajudicial executions to build pressure for police reform. He is the national coordinator of the People's Health Movement in Kenya, which promotes the human right to health. Since 2020 he has been working for the NGO SODECA (Society of Development and Care), which campaigns for the human right to health in marginalised communities.