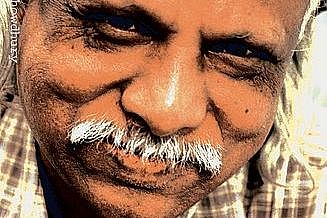

"Health for All" is this year's theme for the 75th anniversary of the World Health Organisation, which was celebrated on 7 April 2023. Only four days later, Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury, who had made "Health for All" the driving force of his own long life, died. Until the end, he was one of the most inspiring figures of the People's Health Movement (PHM), founded in 2000, with which medico international is closely associated. He and the organisation he co-founded, Gonoshasthaya Kendra (GK) in Bangladesh, were and are project partners of medico for many years. Together with his relatives and the colleagues of GK, we mourn the loss of a friend, a partner and an icon of the health movement in the global South.

When we contacted GK in 2006 to discuss options for expanding their non-profit drug production to include AIDS medicines urgently needed in the Global South, we were surprised to discover that our connection went back much further - to GK's founding history as a field hospital for injured fighters in the war of independence against Pakistan in 1971, in which also volunteers from medico international provided emergency aid.

Zafrullah had shortly before co-founded the Bangladesh Medical Association in London, which supported the independence of the former East Pakistan, and then unceremoniously abandoned his own specialist training in London to organise help on the ground. Help at close quarters was his passion, and he spared no risks for it. This, too, connected him with medico.

After the end of the bloody war, in 1972 the field hospital became the "People's Health Centre", Gonoshastaya Kendra, on a site of many hectares in Savar, which at that time was still a whole day's journey across several rivers and tracks from the capital Dhaka, and today lies in the prospering textile industry belt of Bangladesh. Zafrullahs acquired reputation as a freedom fighter helped him in the negotiations with the first president and "father of the nation" Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who made available a large part of the land to GK. Equally important, Zafrullah and his colleagues became convinced in practice that a lasting improvement in health care and health conditions in Bangladesh was not possible with the medical knowledge he had acquired in London alone, but required a completely different way of working

Locally trained and knowledgeable "community health workers" and not academically trained doctors thus still form the core of GK's concept of bringing health to the people and creating it together with them, and not waiting for them to come to the institution when they have already become ill.

In this way, GK, together with other similar health programmes, formed the early pioneers for the Primary Health Care concept as early as the 1970s, which was finally established as the new guiding principle of the WHO and its member states at the major international conference in Alma-Ata in 1978.

This close link between local health practice and international health policy was to continue to characterise the work of Zafrullah and GK. In the 1980s, he successfully fought for pharmaceutical legislation in Bangladesh that consistently focused on rational market control and the promotion of local production. This approach was also finally pushed through at international Level with the important WHO Program on Essential Medicines, even against strong resistance from pharmaceutical companies from the global North.

At the same time, GK proved with its own production of medicines that this was also possible and feasible under the conditions of a non-profit structure. In doing so, it made more than a few enemies. GK's facilities were often subjected to hostility, including an arson attack on GK's second hospital, which they had built up as an urban foothold in a peripheral district of the capital.

Fortunately, this did not permanently hinder GK's work. The organisation grew steadily until it now reaches almost 1 million people with its health and education services. This exemplifies Zafrullah's approach, which he shared with us at the Poverty and Health Conference in Berlin in 2007, to which we invited him together with other PHM representatives: "Small is beautiful, but big is necessary".

In a country with over 160 million inhabitants, this is a comprehensible strategy. With this outreach, GK was not only able to assert itself in Bangladesh as an important player in the often conflicting history of governments and local civil society, but also to prove with facts and figures the effectiveness of its health work. Reductions in child and maternal mortality were thus achieved much earlier and better in the communities where GK had been working for many years compared with the national average.

The consistent promotion of women as employees in GK and not only as recipients of health services has undoubtedly played a significant role in these successes. Not only as paramedics in the health programme and as teachers in the kindergartens and schools were and are women active in GK, they also drive the vast majority of the ambulances after being trained in their own driving school - a feminist mobility revolution in a still largely conservative Muslim country.

International recognition was also forthcoming and Zafrullah was awarded the Ramon Magsaysay Award (the "Asian Nobel Peace Prize" named after the Philippine President) in 1985 and the Right Livelihood Award (the so-called "Alternative Nobel Prize") in 1992.

A special moment in this long history of local and international health struggles was the first People's Health Assembly in 2000 at GK's purpose-built conference centre in Savar. About 1500 activists from all over the world, among them the legendary former Director-General of the WHO, Halfdan Mahler, whose legacy was the Primary Health Care Declaration of 1978, debated and finally adopted the "People's Charter for Health", which reminded the WHO and its member states of the goal they had set themselves in Alma Ata: "Health for All by the year 2000". However, the comprehensive social, political, economic and ecological conditions for health, which the Charter placed at the centre, had to be reminded of the WHO again and again and led to the Commission for Social Determinants for Health 2005 - 2008 with the participation of prominent PHM representatives.

With his experience and infectious enthusiasm, Zafrullah was always able to inspire his colleagues and international supporters for the next project, the next idea. His consistent commitment to equality and justice also made GK a place where marginalised and excluded people found space and participation. For the small Hindu minority in Bangladesh, too, the consistently religion-free space in GK was an important shelter.

Its radical no-smoking policy in all GK facilities and grounds, however, was not necessarily always universally popular. The Brazilian pharmaceutical expert Eloan Pinheiro, for example, whom we invited to Bangladesh in 2006 for an analysis of GK's drug production capacities, had to obtain an exemption for herself as an active smoker for the duration of her stay at GK.

Even though he modestly always introduced himself only as "project coordinator", Zafrullah‘s central role as founder and leader of GK was unchallenged. Until the end, even without official office in GK, Zafrullah was a leading figure whose advice and decisions remained indispensable. This made it equally challenging to find lasting succession arrangements. However, the stability of the GK organisation had already been proven in recent years, when Zafrullah, increasingly ill, had withdrawn more and more from responsibilities.

The conditions for critical global health work have not become any easier, neither locally nor internationally. The death of Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury leaves both a gap and a mission in this challenging time.

We also consider ourselves fortunate to have known Zafrullah and GK for such a long time. He was and remains an inspiration and reminder of the possibility of change for the better, even under adverse circumstances.

Andreas Wulf, medico international