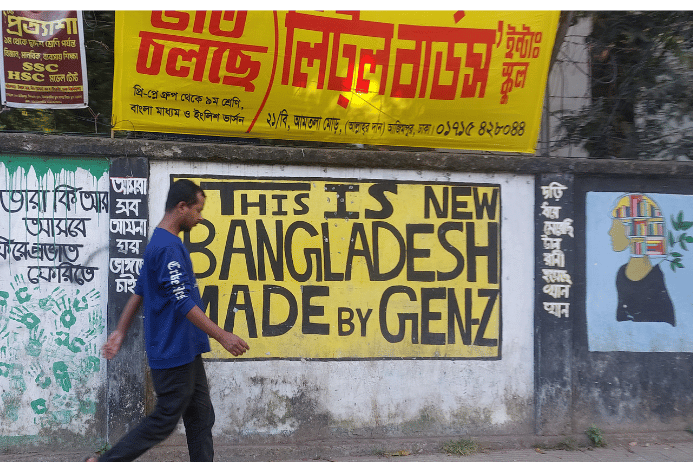

Until now, Bangladesh had only made it to the global spotlight through extreme weather like hurricanes in the Bay of Bengal or man-made disasters, such as the collapse of a textile factory in 2013 that killed hundreds.August 5, 2024, changed this dramatically. Originating from student protests against unfair job allocations in the public sector, and further driven by harsh repression by state security forces that initially left dozens, then hundreds, dead and injured, a nationwide protest movement against the government developed within a few weeks in July 2024. The Awami League (AL), the party of the country's historic founder, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, had led an increasingly autocratic government for 15 years under the leadership of his daughter, Sheikh Hasina.On August 5, the protest movement finally took over the streets of the capital, Dhaka, and laid siege to the Prime Minister's office.When the military refused to continue supporting the unpopular government against this uprising, she and her closest confidants fled in a helicopter in the middle of the night to neighbouring India.She has remained in exile there ever since, and thanks to the support of the Indian government, she has so far been spared extradition to her homeland.At home, she faces trial for years of corruption and responsibility for over 1,000 deaths during the protests.

The Downside of the Uprising

Even though the high-strung rhetoric of the summer of 2024 compared the fall of the regime repeatedly to the 1971 independence struggle against Pakistan, the protesters, unlike in the historical debate among themselves, were by no means united about the path and goal of a "new" Bangladesh. For many workers in the economically dominant textile sector, the immediate consequences of the 2024 coup were fatal.In the first few months afterward, there were massive insolvencies and bankruptcies of large companies that, under the AL government, had unlimited access to loans from state banks and were able to safely transfer staggering profits abroad.The workers' strikes and militant protests over unpaid wages and layoffs blocked the streets in the important textile belt around the capital for months.The transitional government primarily sought to stabilize the banking sector and provided assistance with some direct government loans and social benefits for those laid off. The increase in direct remittances from migrant workers, which increased significantly in the second half of 2024, also limited the social consequences of this crisis, at least temporarily.Bangladesh's foreign exchange reserves halved to just USD 22 billion, but real wages continue to be threatened by the relevant inflation of approximately 10 percent.

The US tariff dispute is not exactly helping in attempts to save the textile industry as its most important export sector.Negotiations have at least succeeded in reducing tariffs on Bangladesh's exports from the originally announced 37 percent to 20 percent, bringing the tariffs in line with regional competitors Vietnam, Sri Lanka, and India.This may seem small given the larger margins for other regions of the world, but the US is the largest buyer of "ready-made garments" from Bangladesh, even ahead of Europe.Furthermore, at the end of 2026, Bangladesh will be promoted from the group of least developed countries (LDCs) to a "normal" developing country due to years of economic growth.In the future (starting from 2029), the country would no longer benefit from the EU's preferential import policies for LDCs.

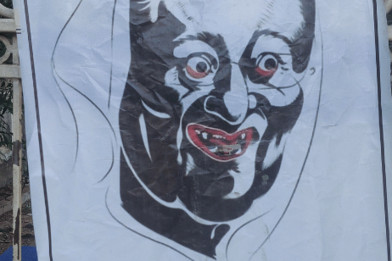

At the same time, conflicts escalated in many places between the two parties that have dominated Bangladesh's political landscape for decades.The Bangladesh National Party (BNP), supposedly "victorious" after the fall of the AL, has fueled renewed attacks on former representatives of the ousted state party.This took on an additional sectarian notion, as the Awami League, with its historically socialist background, was also considered a party of religious and secular minorities (especially the approximately 8 percent Hindu population), who, after the fall of Sheikh Hasina, found themselves exposed to the wrath of the Muslim majority, being identified with Sheikh Hasinas supporters in the Indian Government.Hindu temples and businesses were burned in the aftermath of the change of government.

During the months-long debates surrounding the election date for a new parliament and government, the BNP in particular repeatedly pushed for an early election date and exerted pressure on the transitional government and the National Citizens Party (NCP), newly founded by students in March.As the only major party remaining after the government's fall, the BNP has all the structures and resources in place to benefit from a short-notice election date, while other political actors are still in the process of establishing themselves like the new NCP, or have a more limited support base, like the islamist parties. The NCP would need time and capacity to build party structures suitable for a nationwide election campaign.Otherwise, the elections would be without real competition to the BNP, especially since the handful of small, left-wing parties, despite a joint electoral alliance, have no real basis for potential electoral success.The existing first-past-the-post electoral system in Bangladesh has always favored the two major parties, the AL and the BNP, in the past.It's no wonder that the BNP is primarily committed to preventing a switch to proportional representation.

Struggle for National Self-Perception

Beyond the election debates, the call to express a "new Bangladesh" through a new constitution is growing ever stronger.Such a constitution should not only establish August 5th as the second founding date of the republic, alongside the 1971 founding date of the independent Bangladesh, a demand primarily raised by last year's protest movement to honor its dead and victims.Throughout the country's 54-year history—or more accurately, the 73-year history since the partition of "British India" at the end of the colonial era—the country's self-concept and identity, spanning languages, religions, and ethnic groups, has always been at contested.

The decolonization of „British India“ in 1948 created the new state of Pakistan from the predominantly Muslim areas alongside India. This new state had two parts: one in the northwest, which is present-day Pakistan, and the other in the northeast, „East-Pakistan“, which is present-day Bangladesh.Millions of Hindus and Muslims were forced to flee and were expelled, finding themselves on the "wrong" side of the borders between these two states.Four million people died in massacres on both sides.In Bangladesh, The Hindu minority shrank from over 20 to today less than 10% of the population, mostly fleeing to India’s Westbengal state. Still, Hindus are the largest religious minority today.The Bengali secession movement in the 1950ths and 60ths, which would lead to the founding of Bangladesh, was, in contrast, essentially regionalist and linguistic in nature.Bengali-speaking East Pakistan felt oppressed and exploited by the predominantly Urdu-speaking, Punjab-dominated elites (and their military) in the west of the country, and the early demands for greater autonomy escalated during the 1971 War of Independence. The dominant party, the AL, which secured India's support for this struggle, created the new Bangladesh as a "national, democratic, secular, socialist country." At the same time, subsequent governments, including military regimes, implemented significant changes, including declaring Islam the state religion.The issue of the rights and recognition of religious (Hindu, Buddhist, Christian, and traditional) and ethnic minorities (especially in the east along the borders with Myanmar and in the north with India) by the Muslim Bengali majority remains a contested field, as has also become apparent in recent months. These tensions were exemplified by the violent protests on the streets of Dhaka when the term "Adivasi," with which many indigenous groups in the mountainous periphery identify, was removed from the cover of a schoolbook, symbolically limiting the diversity of Bangladesh's inhabitants.

Even though during the AL governments the minorities also experienced discrimination regarding land rights and political representation, this founding party of Bangladesh was and continues to be considered the (historical) guarantor of a "Bangladesh for all," not just for the Muslim Bengali majority.

There is similar resistance to the efforts of the Islamist party Jamaat-e-Islami to give the new constitution a clear Islamic character. The danger is real;as the third-largest party formation in Bangladesh, the Islamist Party Jamaat-e-Islami acted as a "kingmaker party" in the coalition with the BNP in the early 2000s, repeatedly pushing to roll back the secular character of the founding constitution of the 1970s and is already pushing through the declaration of Islam as the state religion.

Smaller left-wing parties and many human rights organizations are deeply concerned about this. Amidst this conundrum, two events occurred in rapid succession that could hardly have made the incomplete nature of the change process and the turbulent expectations of diverse population groups during this transition clearer.

Uncertain Future

On July 16, the anniversary of the first major student protests in 2024, the newly formed NCP planned a large rally in Gopalganj, the birthplace of the former Prime Minister, to symbolically demonstrate the end of AL rule.A large number of AL supporters attempted to prevent this by blocking roads.The subsequent police deployment to disperse the protests left several dead, prompting even supporters of the "new Bangladesh" to angrily criticize the actions of the security forces.This was the largest confrontation with supporters of the old AL regime, although it remained unclear whether it was orchestrated by leaders from safe exile or whether it was more of a spontaneous local eruption.

What future role the AL might play in Bangladesh remains unclear. So far, at least, there have been no attempts by AL cadres to distance themselves from the authoritarian policies of the former prime minister and her government, or to establish a new party.It seems unlikely that the AL will be able to participate in the elections scheduled for winter.Only in May 2025 did the interim government ban all AW activities under the Anti-Terrorism Act and intends to indict the party for the crimes of July/August 2024.

The second shock occurred only a short time later: A young pilot in an aging fighter jet lost control of his plane while approaching Dhaka Airport, which is also used by the military and has long been surrounded by the city, which has been growing rapidly for decades.The plane crashed like a bomb into a school on the outskirts of the airport in the middle of the day. Over 100 children and teachers were injured, many with severe burns and taken to overwhelmed hospitals.So far, 33 people have been confirmed dead. Pain and shock were followed by anger: at the recklessness with which this disaster was accepted, even though the training flights should have been relocated to rural air force bases long ago, but the money for it is still lacking.

But also anger at the inability of the military and the authorities to truly assume responsibility, beyond symbolically lowering flags at half-mast and declaring national mourning.Anger at politicians who, along with their entourage, staged a show in hospitals and announced generous compensation for the bereaved families, yet the exact number of dead and injured remained unclear for days after the disaster. The fact that this anger can be expressed so freely in the press and the public is a clear sign that last year's coup was both necessary and effective.Prior to this, any criticism of the Prime Minister, her policies, and the military was met with massive persecution.Our partner GK, whose founder openly opposed autocratic policies and therefore repeatedly felt the effects of administrative pressure, also experienced this.

However, it is doubtful whether the sacrosanct status of the military, which has provided several military governments since the War of Independence and ultimately played a decisive role in the overthrow of the old regime last year, can truly be challenged. With last year's revolution, Bangladesh embarked on a new path, the perspective and direction of which, however, remain uncertain.Beyond the rejection of the old AL regime, which they call "fascist," and its pro-India policies, the policies of the new student party, the NCP, remain unclear. Some observers see them as more of a younger version of an Islamist party, although they describe themselves as "centrist and pluralist," rejecting the old term "secular" because it was used to persecute Islam in Bangladesh.What exactly they mean by "centrist," however, also remains vague.

The role of the traditionally strong civil society and its large NGOs is also difficult to assess from the outside. Yet, like few other actors, they stand for the defense of the rights of marginalized groups and minorities and for social justice, just as medico's partner, Gonoshasthaya Kendra, has not given up on the right to a better and healthier life for decades. The current situation is undoubtedly still open.It remains to be seen which forces will prevail.However, the country is united by the experience that an autocratic government can be overcome. And that social conditions do not have to remain as they are forever.