Community work with survivors of the Guatemalan massacre

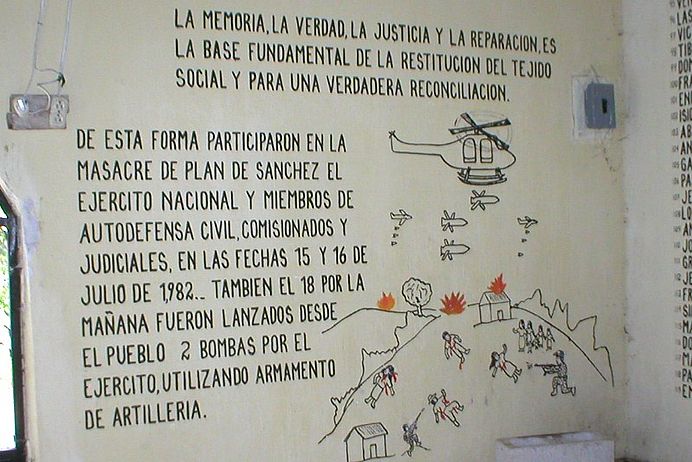

Guatemala’s new president Colom, who took office in 2008, has an undefined number of problems to solve, according to a UN Human Rights Commission report published in the same year. Besides ranking worldwide amongst the countries with the most unequal distribution of wealth, there is, in particular, the matter of violent, organised crime infiltrating the political system itself. Guatemala, says the report, has one of the world’s highest murder rates. This bleak picture forms the backdrop to the health and psycho-social work carried out over many years by Medico’s partners in Guatemala. Work of this kind must take the violent environment into account, the more so as psycho-social work means a methodological orientation that considers both the subjectively felt life realities as well as the sociocultural (economical, political, social and cultural) conditions. In the context of globalisation processes which, particularly in countries like Guatemala, exclude whole swathes of the population by means of direct or structural violence, many people’s subjective realities are the result of countless, traumatic experiences. In Guatemala, this includes a civil war lasting over 10 years accompanied by genocidal persecution of the indigenous population and the continuous escalation of criminal violence up to the present day. How the work is carried out, what can be changed or achieved by it and its meaning for victims of violence is described in “Florecer” (blossoming, flourishing). Developed by our project partner of many years, the Community Research and Psycho-social Action Group (ECAP), Florecer’s very publication in the midst of Guatemala’s apparently disconsolate situation demonstrates alternative ways of dealing with violence and trauma. The book gives a detailed account of the long fight to punish the generals responsible for massacring the indigenous population and their lengthy trial. In the early 80s the army and its death squads had pursued a scorched earth policy. Over 400 villages were wiped out. Hundreds of thousands fled to Mexico or were forced on the run in their own country.

Rebuilding social structures

Drawings, photos and documents record the trials and survivors’ efforts to come to terms with the past. On the front page we see flowers and a tree with an enormous, green canopy. “Florecer” – the name itself was given by a woman from the Ixil triangle, a region in the Quiché province that witnessed many massacres. During one of many therapy sessions for massacre survivors she said, “We are here to blossom again.” ECAP psychologist, Margarita, (the name has been changed for security reasons) explained, “We heard people making this association time and again. They destroyed the tree but not the roots, and now it is time for the tree to blossom again and bear fruit, hence the title.

Furthermore, we consciously chose a positive, powerful element to help people deal with the eight-year trial, a process Medico supported from the outset.” The cooperation with ECAP began in 2001 when survivors of several massacres in the early 80s joined forces with Guatemalan human rights lawyers to bring charges against the former army commanders. ECAP was asked to provide psychological support for witnesses and their support groups. Medico provided the financial support. Admittedly, none of the former generals has yet been found guilty; nonetheless, the survivors have achieved a great deal. “Florecer” testifies to this. The response to the book from those affected has been incredible, comments Margarita. For them, it is important to record the story of people’s own struggles, the fight for justice and the fight to restore the dignity of the murdered, the disappeared and their families. “Florecer” testifies to how social structures are rebuilt as individuals and society deal with their past.

A manual for legal action in the future

A landmark event in Florecer’s chronological accounts is the condemnation of the Guatemalan state by the Interamerican Court for Human Rights. For the first time, a court had ruled in favour of the survivors, giving the injustice official recognition. In terms of dealing appropriately with the severe trauma still suffered not only by the victims and their families, but also, to some extent, by Guatemalan society as a whole, this trial was crucially important. This holds true even though no general was personally held to account. ECAP produced the psychological expertise for this and other trials as the plaintiffs felt that, in addition to proving the murders, it was very important to prove both the material losses suffered and the psycho-social harm caused individually and collectively. For example, the fact that communities had ceased to practice their Mayan religious rituals. This was no easy undertaking, since clinical classifications had to be used and justified; something that Medico and others have repeatedly criticised, as this system fails to reflect the events’ complexity and the consequences. Widespread interest in ECAP’s work, not just in Guatemala, but also in Peru, Mexico, Chile and Columbia led to the idea of a manual. Thus, the methodology used during three years of theoretical and practical work could be made available to others.

Medico granted € 7,890 to produce the manual in 2008. The aim is to help victims of human rights violations elsewhere in Latin America to take their cases to the courts.