medico: In the wake of their withdrawal from Afghanistan, international troops have left behind a disaster. Now Western governments are also casting doubt on the Mali mission. Following the second coup at the end of May, France’s President Macron announced his intention to withdraw his troops from Mali. What is your assessment of this?

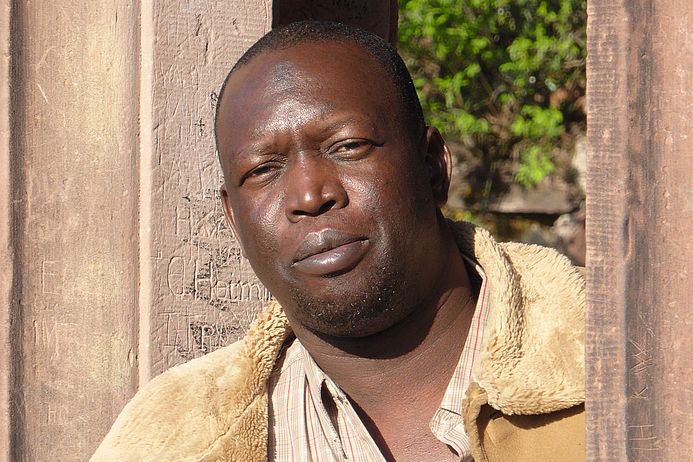

Ousmane Diarra: A very large part of the population wants just that: for France to completely withdraw. If they were only to partly withdraw, France would continue to pursue its real interests - exploiting Mali’s resources such as gas, uranium and gold. I personally am unsure as to what the consequences of a withdrawal would be. It is also difficult to judge to what extent the situation here is comparable to that in Afghanistan. What is clear though is that France’s presence harbours no advantage for the people in Mali. Strategically and politically, it would be important to have other partners. Many would like to see Russia assume this role. There are historical reasons for this – after independence in 1960, Russia was an important international partner to Mali, alongside a few other countries. It was not until later that the former colonial power of France took over the helm again.

What does the population expect from a new partnership with Russia?

When Mali cooperated with what was the USSR at the time, the Malian army was strong. Leaders were trained in Moscow, weapons and equipment came from there. Now, by contrast, the Malian army is very weak. People believe that with Russia’s support that would change again. And with a strong army of its own, Mali would no longer be reliant on international protective powers and neo-colonial partnerships.

Strong and well-equipped national armies in the region that can also put the jihadists in their place - that was precisely the self-professed aim of the interventions by the UN and EU countries.

There is still a strong international military presence. But this has no positive impact whatsoever. The MINUSMA mission has a very bad reputation among the population; people simply don’t want to hear anything about it anymore. The fact is: in spite of the presence of international forces and in spite of training support, nothing has changed for the better in Mali. Quite the opposite, the jihadists are everywhere. There are abductions, the security situation has deteriorated in general and the population’s expectations are not being lived up to. As a result, the missions have lost their credibility.

At the end of May, the Malian military toppled the government for the second time in nine months. A transitional government tolerated by the generals is now to organise the road back to the rule of law. How would you describe the situation in the country right now?

In the wake of the two coups d’état, the national authorities basically no longer have any control. This exacerbates the security situation, which continues to be precarious in the north and south alike. Abductions are increasingly frequent. In the centre, so in and around Bamako, there are clashes between the political parties. The M5-RFP movement, which contributed to toppling President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta in 2020 with its months of protests, continues to play a major role, as do the religious players.

Are the Malian people pinning their hopes on the military because the civilian governments have not managed to improve the situation of the people?

The population is divided on how it views the coups d’état, with one part supporting them and another not believing that a coup d’état can be in the interests of the people. This view has now also been vindicated. The M5 movement, a mixture of forces from politics, civil society and religion as well as the youth movement, was initially a kind of giver of hope. It championed the government’s term in office coming to end normally and did not want a coup d’état. But once the president was forced to resign, M5 also wanted a share of the power. The movement allowed itself to be incorporated into the military government. This is further proof that they are all just pursuing their own personal interests and not those of the population. A coalition of different political actors, including the left-wing party SADI recently made this point: In Mali, there is a silent majority whose position is not reflected by the ruling factions or in the protests. This majority wants the transitional government to design a process that will lead to transparent elections.

After the first coup, it was agreed that elections would be held in February 2022 so that a new legitimate government could be formed. Since then, the first interim government has been deposed. Officially, however, the date is still valid, especially since there is pressure from abroad - not least from Europe – to hold elections. How do you see it: is it desirable for elections to be held soon?

It is uncertain whether elections will take place in February 2022. I would say: they can’t happen that quickly, at least not if the elections are supposed to be fair, transparent and correct. The parties have not yet presented specific manifestos. Above all, the transitional government is not equipped to set the necessary processes in motion. The international powers are insisting on the February 2022 date because it was agreed at the time that the military would have to hand back power no later than 18 months down the line. However, the pressure to hold elections then at any cost only increases the risk of another coup and does not alleviate the pain of how things are.

Interview: Sabine Eckart and Ramona Lenz

Translation: Rajosvah Mamisoa

The German Bundeswehr is also deployed in Mali, in the context of “counter-terrorism”, stabilisation and the EU’s efforts to frustrate migration in and out of Mali and the whole of West Africa. At the same time, the situation remains extremely precarious. In this situation, medico is promoting migrant self-organisations that support rejected migrants by providing them a roof over their heads and working with them to develop prospects.