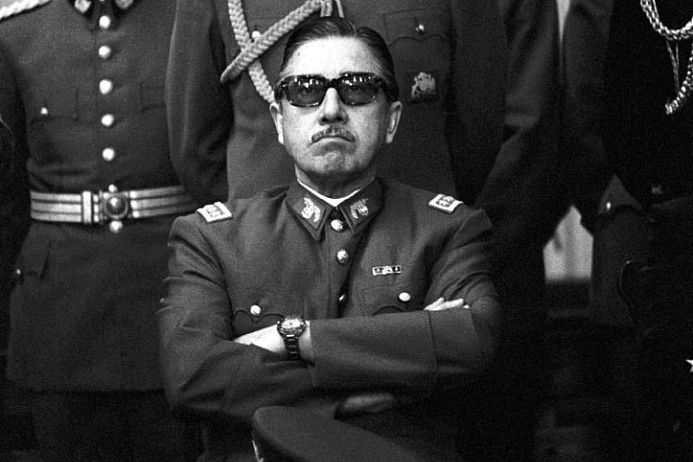

If Augusto Pinochet were still alive, he would probably be thrilled at the state of the world, and especially of the masses, as we mark the 50th anniversary of the coup in Chile. Whilst back in his day he had to stage a coup against a socialist government and a confident society with the help of the military and the CIA, nowadays authoritarian leaders in large swathes of the world can rely on political majorities or at least know that they are within reach. Not just in Chile.

Nowadays the authoritarian threat by no means just comes from the top. This is perhaps what is most menacing about what has been happening in many countries and regions of the world for some years now. There is a distance to the institutions of an often bourgeois political culture which does not nourish social alternatives, but rather is mobilised as anger towards these. And there can be little doubt that what is brewing is the potential mass base for a new form of fascism.

Despite all the differences, this is a global phenomenon that connects the West and the East. Not just India or Russia have authoritarian governments. Italy has a right-wing government with several professed fascists in its ranks. France is on the cusp of Le Pen, the US only narrowly and only for the time being escaped a second Donald Trump presidency. And in Germany, too, the AfD is now the strongest party in some regions and is developing into a major party nationwide. The German and European East are in a dramatic social situation; whilst the armament of Ukraine in defence of democracy and freedom is orchestrated by the media, there is a depressing silence about the nationally liberated zones in our own front yard.

Authoritarian liberalism

Whilst since the start of the Ukraine war, Western-style neoliberalism has been styling itself with renewed vigour as values-based liberalism and a geopolitical bulwark against Eastern-style authoritarianism, in political theory the processes in Chile 50 years ago have been described as “authoritarian liberalism”. Not just a linguistic coincidence: the assertion of neoliberalism and the planned transition of the dictatorship to a neoliberal democracy were based on a strong state whose political powers were the police and the military. In the coup, they eliminated the countervailing social forces: the left, trade unions, public welfare institutions and virtually all other popular groups. The suppression of all these power resources of a population seen by the elites as an “ungovernable society” violently created the framework in which the model of neoliberal freedom of the economy and private existence was then established.

The disempowerment of society and the community, which leads to life being lived almost exclusively within the command of capital and as an isolated private existence, was the defining action of the neoliberal model of society, enforced by power and violence. The paradise of work, consumerism and private pleasure is preceded by the violent political disempowerment of the people. It is worth recalling this now: as the Russian war of aggression began to unfold, I was in Chile with some medico colleagues. When asked what they thought of the newly emerging geopolitical challenge, in which the liberal West was defending itself against an authoritarian East, the Chileans replied succinctly: “That’s not a problem in Chile. Here, the two go together.” The ingredients of neoliberalism are liberalism and authoritarianism.

Understanding the right-wing rebellion

The storming of the Capitol, Pegida or Bolsonarism: the connection between authoritarianism and liberalism is also key to understanding the right-wing authoritarian revolt. But the debate about this in this country is not only glaringly superficial, since the start of the Ukraine war it has often only taken place in the sidebar. It does not fit the new geopolitical distribution of roles. Erich Fromm once described this as political projection: “The essence of projective thinking is projecting the evil within us onto an external figure, so that this figure becomes the epitome of evil, whilst we ourselves are perfectly good and pure. This projection mechanism is usually effective in war”.

But the geopolitical situation and this new evocation of liberalism, this time with the prefix neo, can barely conceal the fact that it is once again an endeavour that is self-destructing. And not for the first time either. In 1944, Hannah Arendt wrote an essay on the mass base of fascism. At that time, she saw it residing not just in barbarian hordes, but also in the unleashed “bourgeoisie”. Not Hitler or Göring, but rather Himmler was the sociological prototype of cruelty in her view. For her, he is a version of the bourgeoisie cut off from any relationship to the world and committed only to the pursuit of private and family interests. For Arendt, Germany was an excellent breeding ground for this, not because brutality and fanaticism here were so huge, but because the role of the private sphere was so great and the public sphere historically so underdeveloped.

It was not political fanaticism, but in fact egotism and a turning away from the wider world that created the Nazis’ mass base, “behind the chauvinistic pretension of ‘loyalty’ and ‘courage’ lies a fateful tendency towards disloyalty and betrayal out of opportunism”, so Arendt. People had their fingers more on today’s pulse then than they do now: the question of how the bourgeois can turn into the authoritarian, how quickly the seemingly unbridgeable distance can be bridged, was rightly front and centre. Max Horkheimer’s phrase “If you aren’t willing to talk about capitalism, you had better keep quiet about fascism” is also symbolic of this. But what can it mean today? At least perhaps that the right-wing rebellion is also an expression of a neoliberal subjectivity that simply no longer believes in the promises made and is now aggressively turning against them, against “the powers that be”, who they feel betrayed by.

Sovereignism and self-disempowerment

However, it does not help to meet this authoritarian revolt with a highly armed bourgeoisie. Is there still a shared world or is it everyone for themselves? This question must also be asked of the centre, whose way of life and saturation only in its own milieu can be presented as the result of a value-based model of life that must be defended against evil. For others, it is quite simply the defence of a world that is inaccessible to them. And sometimes one has the impression that the moral armament is less about combating the right and more about not having to really change one's own habits and beliefs in any meaningful way.

And this is where another problem begins. Notably, that of the authoritarianism of the centre in its reaction to the right-wing rebellion. It not only fails to recognise its own part in the emergence of the new right, but also its own authoritarianism. Just think of corona, in a sense an inflection point. The authoritarian rebellion by some was followed by the authoritarian invocation of order and security by others. True, this authoritarianism comes with a soft voice because it enjoys the power of the strongest. But not for a long time has it been as armoured with coercion as it is today. Even in the world of corona, an authoritarian pivot was apparent in liberal circles, as shown not just by sociologist and physician Karl-Heinz Roth. Even for parts of civil society, there seemed to be no other political force than the nation states any more, and the authority of their government, leaders and law enforcement.

This sovereignism and the mental self-disempowerment of the population continues seamlessly with the transition to the war in Ukraine and the primacy of geopolitics. Here, all of a sudden, people are fighting for democracy and freedom in alliance with armies, nationalists and arms corporations, not out of desperation, but with passion. One may see this fight as inescapable. However, to load it with pathos and give it the face of innocence, instead of understanding it in all its cruelty, will perhaps have unforgivable consequences. The most tangible at present is that a recent report published by the New York Times now speaks of 500,000 dead and wounded in connection with the Russian attack on Ukraine. Free the leo. “I am concerned about the indifference towards life and the brutalisation of humankind, which have grown ever greater since the First World War,” to cite Erich Fromm once again.

Heading for dark times

Brutalisation and militarisation are not being preached by everyone, but nevertheless seem increasingly inevitable. This is not the only reason why there is an urgent need to understand the overarching authoritarian dynamic that has taken hold not only of political spectrums but of entire societies. The fact that little is being done to counter this from the left has to do with the fact that the left itself has long been mired up in it.

We must not underestimate all this as merely a superficial phenomenon or symptom, we need to understand it in all its depth and self-reinforcing tendencies. In a world full of war and catastrophes, we are facing not just ecological collapse, but also mental demise. Anti-fascism, in the sense of a serious awareness of this threat, is not the only, but nevertheless a key imperative of our times.

The triumph of neoliberalism takes the form of a political defeat of all social forces with a subjective message and the associated societal consequences. The temporary end of the imaginary and utopian, the end of all dreams, the tyranny of the real, of the feasible is the sad prison we are all caged in: a social and political programme to shatter anything we share as a community and to leave only the individual at the mercy of the market and its institutions. No values can help against this.

Hannah Arendt’s essay ends with the conclusion that humanity is a real burden for humankind. Believing in it is infinitely more difficult than signing up to imperial and national politics. How can you conceive global anti-fascism with empty hands? “This fundamental shame that many people of all different nationalities share with each other today, is the only thing we have left emotionally of the solidarity of the international sphere; and it has not become politically productive in any way thus far.” Perhaps by this she meant no more and no less than the refusal to join all those collectives and rationales whose foreseeable fate is the battlefield and civil war.